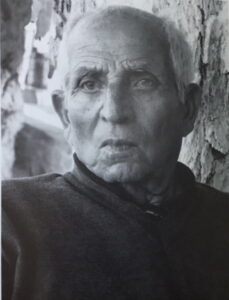

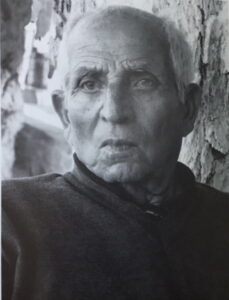

One of a series of snapshots by Bob Bowden – a long-time resident of the village of Diafani.

The tragedy

On 21st September, 1943, a Baltimore 575 long-range bomber was sent on a reconnaissance mission over the southern Aegean by the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force). It carried a crew of four: Pilot Warrant Officer Peter Kennedy, wireless operator and turret gunner Flight Sergeant Noel Fisher, wireless operator and rear gunner Sergeant Jack Ganly and navigator/bomb aimer Alvin Liebick.

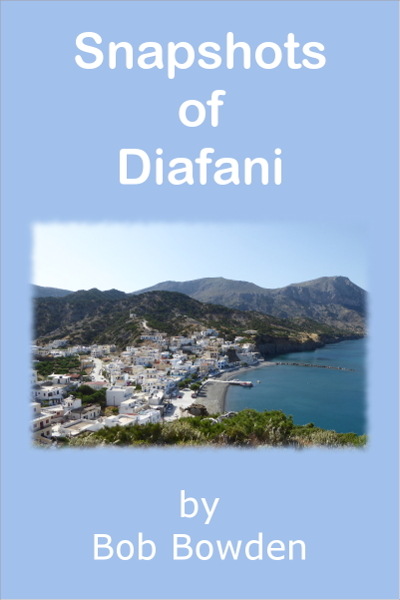

A Martin Baltimore bomber note 1

A Martin Baltimore bomber note 1

The aircraft failed to return and the conjecture was that the crew had had too little practice in low flying in what was a difficult aircraft and had hit the sea, or, engine trouble had led to it diverting to Turkey or Crete. The following night a light was reported flashing from the sea south of Karpathos and an extensive search was carried out by Air Sea Rescue without success.

In fact, the plane had been hit by anti-aircraft fire, causing the port engine to cut, and the aircraft hit the sea, bounced, turned sideways, came to a halt and sank. Peter Kennedy recalled:

“We were flying low when gunfire led to us ditching. We climbed into the aircraft’s inflatable dinghy, which floated up from the sunken aircraft, and subsequently were taken ashore by Greek villagers in a small boat. When Jack and I pulled Alvin into the dinghy we found that he had suffered deep scalp wounds about 8 inches long and also a badly lacerated and crushed chest (I think broken ribs). He was in such pain that I injected him with 2 ampoules of morphine from the dinghy’s medical kit. After reaching shore at the village of Diafani, our wounds were treated by a Greek doctor who placed 32 stitches in Alvin’s head wounds and bandaged his chest. There was no hospital available.”

During the rescue, Noel Fisher unfortunately lost his life and Jack Ganly sustained a large wound to his head, also treated by the Greek doctor.

While events were unfolding in Karpathos, back at 454 Squadron’s Amiriya base in Egypt, searches were getting underway amid hopes that the crew had survived. Read the official entries from the Squadron’s War Diary.

The story continues in the words of the abovementioned doctor, Dr. Andreas Lambros.

Dr. Andreas Lambros’ account

With the help of the residents of Diafani, we held a funeral for Noel and buried him in the cemetery next to the little church of St Nicholas. We planted flowers around his grave and a small votive lamp was lit every night for his soul until September 30th when the Germans took over control of the island and to pay such respects to the memory of Noel would have been a very dangerous thing.

The Italian volta-face

A large boat arrived from Pighadia with a letter for the Italian non-commissioned officer in Diafani whose senior officer ordered him to hand over the Australian pilots DEAD OR ALIVE. The Italian ordered me to tell the survivors to come to his office as he had something urgent to announce.

Peter reacted furiously and told me to return the message that they would not go to his office, and if he had to tell them anything he should do so from the balcony so everyone could hear. So he came out onto the balcony and said he had received an order to hand the Allied troops over to the Germans. Peter shouted to him so that everyone could hear:

“Do you know that Italy has signed an armistice with the allies?” note 2

“Yes”, replied the Italian.

“Do you know that on the bottom of the armistice your king placed his signature?”

“Yes”, he replied once again.

“Do you know that from this moment on we are allies against the Germans?”

Again, “Yes.”

“Then, why are you handing us over to the Germans and violating your armistice?”

The Italian replied, “If anyone is violating the armistice, it is not I but my superior and I am obliged to carry out his orders.”

It was not possible to disagree with this argument so it was decided to surrender the airmen. We set off for the boat and somewhere along the beach front Liebeck said to me “Doctor, where was our comrade buried?” I showed him the church with the cemetery and all three stood silent on the beach with their head turned in the direction of their friend’s grave for a minute to bid him farewell. If they remember, they will recall that I wept like a child.

The botched rescue

It should also be remembered that we sent a man in a small boat to Symi, where the English already were, to inform them of what had happened in Diafani and to ask them to come and rescue our companions. Four or five days had already passed and we had heard nothing. But we hoped from hour to hour that help would arrive so we told the captain of the boat that we needed to call in at a small harbour and contact the village doctor so that he could come and change the dressings of the wounded. This was not necessary but we were trying to delay our arrival in Pighadia where the Germans were waiting.

We delayed the boat, and the doctor came and changed the dressings, but we were then obliged to set off for Pighadia where we arrived late in the afternoon and they were handed over to the Germans by ‘these Italian pigs’ as Peter called them.

That same night a British commando arrived in Diafani but was forced to hide until daybreak because the Italians were celebrating the armistice by throwing grenades and he thought that some sort of combat was taking place!

Early next morning two soldiers, armed to the teeth, and a civilian came and asked the Italians where the pilots were. note 3 The Italians replied that the Germans had them and at the mention of the word ‘Germans’, without asking how, when, why or where, they ran to the beach as if being shot at! In their haste, and not listening to our advice not to run because the Germans were 50 kilometres away, they took a boat and set off for the boat that had brought them. But the boat leaked and 500 metres from Diafani, it sank. One soldier took off his weapons and the civilian his overcoat and managed to swim to their boat but the other soldier was not so fortunate and drowned. His companions, intent only on getting away, left – and are probably still going!

We saw what had happened and quickly took a boat to the scene of the tragedy, where, after an hour’s searching, we found the body. We brought him back, laid him on the sand and gave artificial respiration and heart massage but without success. We buried him next to Joel.

So, you can see that the delay in arrival of commandoes was fatal and led to the imprisonment of Peter, Alvin and Jack. If they had arrived in time and saved the pilots, they would have continued in the war, if not in the Mediterranean, then elsewhere and, who knows, may have been killed fighting. Their subsequent imprisonment was bitter and their future uncertain but they were fortunate enough to be sent to a prisoner-of-war camp and survived intact to be freed by the Russian invasion of Germany.

After the war

The gratitude of Great Britain and the Commonwealth

Returning home, they paused in London and went to the Air Ministry to relate the assistance they had received in Diafani. Months later I received a parcel from Australia containing sugar, coffee, butter, cheese, corned beef and a clock with the inscription ‘To Doctor Andreas Lambros from Alvin Liebeck for September 1943’.

In July 1946 an English ship arrived in Pighadia and I was sought out. I was taken to a major who spoke good Greek, a lieutenant and a secretary in civilian clothes. The major asked me my name and if during the war I had helped Australian pilots. I told him my name and the help I gave in 1943 and that I had received a letter from Liebick and that if he wanted I could bring it from my surgery. “No”, he said, “we know everything, so the reason we came here is to pay you, Doctor, for everything you did for our pilots and for anyone else you helped because we will never pass this way again.”

I asked the major to translate what he had said for the lieutenant to hear. I then said “I only did my duty as a patriotic Greek doctor just as anyone else in the same position would have done. I do not want any money. I am only sorry that when war broke out, I was not in Greece to fight the Italians in Albania and then Greece fell, not to the Italians but the Germans, I wanted to be in Crete and when Crete fell, I wanted to be in Egypt and, if God had given me time, I would have liked to have marched through Rome and Berlin. That I did my duty and would not accept any money.”

The major, on hearing my words, arose and approached me with tears in his eyes. “What are you Greeks?! Three thousand years have passed since the battle of Marathon and the same blood flows through your veins!”

“Doctor, I have been ordered by Field-Marshal Alexander, to give you the certificate in which is expressed the gratitude and honour of Great Britain and the Commonwealth for everything you did during the war of 1939-1945.”

This I accepted and it is now on my surgery wall, numbered 16091 to remind me always of a good patriotic example. Two other colleagues, Stellios Farmakides and Costas Giannouris received certificates 16092 and 16093.

The family pilgrimage

We now move many years forwards, to June 2013. A lady called Coralie Ganly, the daughter of the brave rear gunner Jack Ganley, living in Cairns, Australia, aware of the facts outlined above from correspondence between the family of pilot Peter Kennedy and Dr. Lambros in the eighties, found the ‘Friends of Diafani’ website. Some of you may have been familiar with this site, which was operated and updated on a regular basis by Margarita Dassas-Appleby, who lived in Paris and visited Diafani for prolonged periods for many years. note 4

Coralie had resolved to visit Karpathos with her partner Steve in October 2013. She approached Margarita after finding the site, explained her interest in finding out more and briefly outlined the background. She was aware that Dr Lambros was 75 in 1983 and had 4 daughters and a son, who had become a pharmacist. She had found a pharmacist in Karpathos called Lampros (the letters ‘b’ and ‘p’ are interchangeable on some occasions in Greek) and, wondering if this was the son, asked if more light could be shed.

With Margarita’s help and the cooperation of several others, a successful outcome resulted and I can do no better than quote Coralie’s email response to my request to pass all this on to you as a tale worth telling:

“Yes. We did meet Elias Lambros the pharmacist, his wife and two sisters and their families. They welcomed us with open arms and together with Margarita and Claude (Margarita’s spouse) they made our journey to Karpathos a very memorable experience. Our visit to Diafani was a highlight of my holiday because 1) I was able to visit the place where my father’s plane crashed 70 years ago and reflect on what he and his colleagues would have experienced as a result of the crash and 2) to pay tribute to Noel Fisher, his colleague who died. My partner Steve and I were overwhelmed by the warm gratitude expressed by the people of Diafani and Olympos. Thanks to Margarita I was able to meet with some of the men who, as little boys, witnessed the plane crash, and to meet the wonderful man who rowed out in a boat to rescue Dad and his wife. I never anticipated that I would be fortunate enough to meet these people and thank them for the kind and brave assistance they gave to my father and his colleagues.”

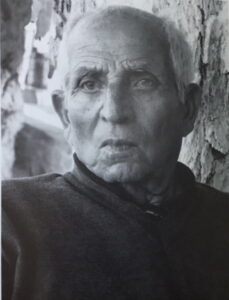

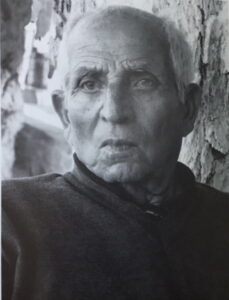

‘The wonderful man’, Kostas Lioreisis

© 2012 Manos Anastasiadis This ‘wonderful man’, then just a lad, now elderly gentleman, Kostas Lioreisis, remembers the rescue very well and has wondered all these years why there was so much paper floating all around them on the sea. Coralie surmised that this was maps relating to the reconnaissance they were engaged on which finally satisfied Kostas’ curiosity. Kostas had subsequently married Fotini who also has vivid memories of the rescue, the men having been housed in her aunt’s house where she took them such food as the villagers could spare. She also recalls that, despite being very wet and cold, the men were determined to maintain military dress and she helped to wash and dry their uniforms. As a couple they later opened a small hotel called ‘Diafani Palace’, which welcomed the first visitors to Diafani.

Coralie Ganly and Mr and Mrs Lioreisis

© Coralie Ganly Update June 2022 – “Secret Statement” surfaces

I completed this tale in 2013. It was sent to Coralie and the network of family and friends on my ‘mailing list’. And that was that. Then this website was created and the stories from Manolis Makris’ book ‘In the Years of the War’, together with this, were exposed to public view. Then naught else happened until in March 2021 when I learned that it had been translated into Greek and published in that week’s edition of ‘The Voice of Olympos’, a newspaper published and printed in Rhodes recounting events of interest to the people of Olympos and Diafani, accompanied by a flattering leader article!

Then, or now rather, Roger Jinkinson, the author of ‘Tales from Laos’ on this site, and the two volumes of stories, ‘Tales from a Greek Island’ and ‘More Tales from a Greek Island’, recounting characters and goings on in Diafani, sent me a document found by a friend of his in the UK National Archives at Kew, which is, in the context, stunning.

It is a ‘Secret Statement’ by A 414481, Warrant Officer John Archibald (Jack) Ganly, 454 squadron Bomber Command, RAF. himself! (Note: RAF! My title was wrong at the very start!) So, literally, straight from the horse’s mouth, I can do no better than quote it in full, with my notes where appropriate, (in brackets), to clarify. The text of the document below has been transcribed from the original held at the UK National Archives note 5 .

1. Evasion and capture

“I was the Wop/ag (wireless operator/gunner) of a Baltimore on a P.R. (photo reconnaissance) in the area of the Dodecanese on 21 Sep 43. We had just completed our recce of a harbour at the south end of the island of Skarpanto (This was the name the Italians gave Karpathos) and had gone about 25 miles up the East coast of the island when the port motor suddenly cut. We were at about 100 feet at the time and we immediately lost height, “bounced” on the sea and then banked steeply, and went into the water sideways. The aircraft sank instantly and when I came to I was under the water. I managed to get out through a crack in the rear of the fuselage. The Captain, W/O (Warrant Officer) Kennedy and navigator, W/O Lebich, had also managed to get out and we all got into the dinghy which had by this time floated free of the aircraft. The other Wop/ag, F/Sgt Fisher did not manage to get out and his body was later recovered by the Italian army personnel who came out for us. We were about 3-4 miles from the shore when we crashed and we could see boats putting out from the shore in our direction, so we sat in the dinghy and waited. It was by this time about 1130 hours. There were three boats in all manned by Italian soldiers and Greek civilians, and while one of the boats took us to the shore the others continued to search for Fisher’s body, which they found some time later. We tried artificial respiration and a doctor was fetched but he was beyond help.

“The doctor was Greek and was very helpful. We were able to converse with him through the medium of French and he spoke to the Italians on our behalf and they agreed not to hand us over to the Germans at Bagardia (the harbour town which we had reached) (Jack had misheard Pigadia, the capital of Karpathos). We were accommodated in the house of a Greek patriot and although food was very scarce they deprived themselves to feed us. Lebich had been severely injured in the crash and had lost a considerable amount of blood and the doctor visited him every day and did everything he could for him.

“Our plan was to procure a boat and endeavour to reach either Cos or Leros. But as Lebich was too weak to be moved we decided that only one of us should go and try to obtain help while the other would remain with our sick comrade.

“On the 26 Sep a Greek patriot arrived in a small boat. He had escaped from Crete and he agreed to take one of us to Leros. However, we were dissuaded by the Italians from making the trip as the boat was a very small one and they did not consider it safe for two passengers. However, they wrote a letter to the Commander of an Italian Garrison on a nearby island asking him to send a motor boat to take us off and our Greek boat owner agreed to deliver it.

“The following morning, however, we were surrounded by several Italian soldiers and it was obvious by their attitude that they had come for us. I managed to make a break and got some distance to the house of a Greek friend but was followed and captured.

“All three of us were then taken by small boat to Bagardia where we were turned over to the German garrison, the journey taking two days.”

2. Camps in which imprisoned

“In transit from Bagardia to Dulag Luft 27 Sep 43

“Dulag Luft. 1 Nov – 10 Nov 43

“Stalag IVB. Muhlberg. 11 Nov 43 – 23 Apr 45”

3. Attempted escapes

“Nil”

4. Liberation

“We were liberated by the Russians on 23 Apr 45”

———-

That’s it. Good to have another account and to know that they all three survived the war. Liberated on St George’s Day. For all who have come to know and love Karpathos, and particularly Diafani/Olympos as tourists, it beggars belief to stand in this beautiful place and conceive of these events. On reflection, I am writing this in my home in Bristol, where I spent lots of my childhood on bomb sites! Wars eh! What the hell are they for?

Epilogue

Please take a moment to pay tribute to all the men and women involved in these events, most of whom are no longer with us. Also, to pay tribute to that still-evident Greek impulse to assist those in need and to show courage in the face of adversity, as was demonstrated in 1943 and bas been reaffirmed during the recent difficult years.

I hope you agree that it is a heart-warming story and I take no credit for it other than assembling the pieces into as complete a picture as possible.

Bob Bowden

Footnote: To my surprise and delight this ‘snapshot’ has been translated into Greek and published in the March 2021 edition of the newspaper Η Φωνή της Ολύμπου (The Voice of Olympos). Read the ‘leader’ article which preceded it.

Leave a comment about this comment

Leave a comment about this comment

Article copyright ©2021 Bob Bowden.

454 Squadron RAAFYou can read more about the operations carried out by 454 Squadron in the book ‘Alamein to the Alps: 454 Squadron RAAF 1941-1945’ by Mark Lax. The book can be read online at www.yumpu.com.

Notes

Note 1: Source wikimedia.org https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:15_Martin_Baltimore_(15812407426).jpg. Uploaded to wikimedia by San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives. This image was taken from Flickr’s The Commons. The uploading organization may have various reasons for determining that no known copyright restrictions exist, such as: 1) The copyright is in the public domain because it has expired; 2) The copyright was injected into the public domain for other reasons, such as failure to adhere to required formalities or conditions; 3) The institution owns the copyright but is not interested in exercising control; or, 4) The institution has legal rights sufficient to authorize others to use the work without restrictions.

Return from Note 1

Note 2: The armistice of Cassibile represented a total capitulation of Italy to the Allies and was signed by King Victor Emanuel III and Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio following the Allies’ victories which had led to the surrender of 13th May 1943 of all Axis forces in North Africa, the Allied bombing of Rome on May 16th and the invasion of Sicily on July 10th with the threat of a landing on the mainland.

Return from Note 2

Note 3: The account does not make clear the nationality of these people.

Return from Note 3

Note 4: Sadly, Margarita passed away in 2014

Return from Note 4

Note 5: The text of the ‘Secret Statement’ has been transcribed from the record held at the UK National Archives. Use of the text is subject to the Open Government Licence.

Return from Note 5

On 21st September, 1943, a Baltimore 575 long-range bomber was sent on a reconnaissance mission over the southern Aegean by the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force). It carried a crew of four: Pilot Warrant Officer Peter Kennedy, wireless operator and turret gunner Flight Sergeant Noel Fisher, wireless operator and rear gunner Sergeant Jack Ganly and navigator/bomb aimer Alvin Liebick.

A Martin Baltimore bomber note 1

A Martin Baltimore bomber note 1

The aircraft failed to return and the conjecture was that the crew had had too little practice in low flying in what was a difficult aircraft and had hit the sea, or, engine trouble had led to it diverting to Turkey or Crete. The following night a light was reported flashing from the sea south of Karpathos and an extensive search was carried out by Air Sea Rescue without success.

In fact, the plane had been hit by anti-aircraft fire, causing the port engine to cut, and the aircraft hit the sea, bounced, turned sideways, came to a halt and sank. Peter Kennedy recalled:

“We were flying low when gunfire led to us ditching. We climbed into the aircraft’s inflatable dinghy, which floated up from the sunken aircraft, and subsequently were taken ashore by Greek villagers in a small boat. When Jack and I pulled Alvin into the dinghy we found that he had suffered deep scalp wounds about 8 inches long and also a badly lacerated and crushed chest (I think broken ribs). He was in such pain that I injected him with 2 ampoules of morphine from the dinghy’s medical kit. After reaching shore at the village of Diafani, our wounds were treated by a Greek doctor who placed 32 stitches in Alvin’s head wounds and bandaged his chest. There was no hospital available.”

During the rescue, Noel Fisher unfortunately lost his life and Jack Ganly sustained a large wound to his head, also treated by the Greek doctor.

While events were unfolding in Karpathos, back at 454 Squadron’s Amiriya base in Egypt, searches were getting underway amid hopes that the crew had survived. Read the official entries from the Squadron’s War Diary.

The story continues in the words of the abovementioned doctor, Dr. Andreas Lambros.

Dr. Andreas Lambros’ account

With the help of the residents of Diafani, we held a funeral for Noel and buried him in the cemetery next to the little church of St Nicholas. We planted flowers around his grave and a small votive lamp was lit every night for his soul until September 30th when the Germans took over control of the island and to pay such respects to the memory of Noel would have been a very dangerous thing.

The Italian volta-face

A large boat arrived from Pighadia with a letter for the Italian non-commissioned officer in Diafani whose senior officer ordered him to hand over the Australian pilots DEAD OR ALIVE. The Italian ordered me to tell the survivors to come to his office as he had something urgent to announce.

Peter reacted furiously and told me to return the message that they would not go to his office, and if he had to tell them anything he should do so from the balcony so everyone could hear. So he came out onto the balcony and said he had received an order to hand the Allied troops over to the Germans. Peter shouted to him so that everyone could hear:

“Do you know that Italy has signed an armistice with the allies?” note 2

“Yes”, replied the Italian.

“Do you know that on the bottom of the armistice your king placed his signature?”

“Yes”, he replied once again.

“Do you know that from this moment on we are allies against the Germans?”

Again, “Yes.”

“Then, why are you handing us over to the Germans and violating your armistice?”

The Italian replied, “If anyone is violating the armistice, it is not I but my superior and I am obliged to carry out his orders.”

It was not possible to disagree with this argument so it was decided to surrender the airmen. We set off for the boat and somewhere along the beach front Liebeck said to me “Doctor, where was our comrade buried?” I showed him the church with the cemetery and all three stood silent on the beach with their head turned in the direction of their friend’s grave for a minute to bid him farewell. If they remember, they will recall that I wept like a child.

The botched rescue

It should also be remembered that we sent a man in a small boat to Symi, where the English already were, to inform them of what had happened in Diafani and to ask them to come and rescue our companions. Four or five days had already passed and we had heard nothing. But we hoped from hour to hour that help would arrive so we told the captain of the boat that we needed to call in at a small harbour and contact the village doctor so that he could come and change the dressings of the wounded. This was not necessary but we were trying to delay our arrival in Pighadia where the Germans were waiting.

We delayed the boat, and the doctor came and changed the dressings, but we were then obliged to set off for Pighadia where we arrived late in the afternoon and they were handed over to the Germans by ‘these Italian pigs’ as Peter called them.

That same night a British commando arrived in Diafani but was forced to hide until daybreak because the Italians were celebrating the armistice by throwing grenades and he thought that some sort of combat was taking place!

Early next morning two soldiers, armed to the teeth, and a civilian came and asked the Italians where the pilots were. note 3 The Italians replied that the Germans had them and at the mention of the word ‘Germans’, without asking how, when, why or where, they ran to the beach as if being shot at! In their haste, and not listening to our advice not to run because the Germans were 50 kilometres away, they took a boat and set off for the boat that had brought them. But the boat leaked and 500 metres from Diafani, it sank. One soldier took off his weapons and the civilian his overcoat and managed to swim to their boat but the other soldier was not so fortunate and drowned. His companions, intent only on getting away, left – and are probably still going!

We saw what had happened and quickly took a boat to the scene of the tragedy, where, after an hour’s searching, we found the body. We brought him back, laid him on the sand and gave artificial respiration and heart massage but without success. We buried him next to Joel.

So, you can see that the delay in arrival of commandoes was fatal and led to the imprisonment of Peter, Alvin and Jack. If they had arrived in time and saved the pilots, they would have continued in the war, if not in the Mediterranean, then elsewhere and, who knows, may have been killed fighting. Their subsequent imprisonment was bitter and their future uncertain but they were fortunate enough to be sent to a prisoner-of-war camp and survived intact to be freed by the Russian invasion of Germany.

After the war

The gratitude of Great Britain and the Commonwealth

Returning home, they paused in London and went to the Air Ministry to relate the assistance they had received in Diafani. Months later I received a parcel from Australia containing sugar, coffee, butter, cheese, corned beef and a clock with the inscription ‘To Doctor Andreas Lambros from Alvin Liebeck for September 1943’.

In July 1946 an English ship arrived in Pighadia and I was sought out. I was taken to a major who spoke good Greek, a lieutenant and a secretary in civilian clothes. The major asked me my name and if during the war I had helped Australian pilots. I told him my name and the help I gave in 1943 and that I had received a letter from Liebick and that if he wanted I could bring it from my surgery. “No”, he said, “we know everything, so the reason we came here is to pay you, Doctor, for everything you did for our pilots and for anyone else you helped because we will never pass this way again.”

I asked the major to translate what he had said for the lieutenant to hear. I then said “I only did my duty as a patriotic Greek doctor just as anyone else in the same position would have done. I do not want any money. I am only sorry that when war broke out, I was not in Greece to fight the Italians in Albania and then Greece fell, not to the Italians but the Germans, I wanted to be in Crete and when Crete fell, I wanted to be in Egypt and, if God had given me time, I would have liked to have marched through Rome and Berlin. That I did my duty and would not accept any money.”

The major, on hearing my words, arose and approached me with tears in his eyes. “What are you Greeks?! Three thousand years have passed since the battle of Marathon and the same blood flows through your veins!”

“Doctor, I have been ordered by Field-Marshal Alexander, to give you the certificate in which is expressed the gratitude and honour of Great Britain and the Commonwealth for everything you did during the war of 1939-1945.”

This I accepted and it is now on my surgery wall, numbered 16091 to remind me always of a good patriotic example. Two other colleagues, Stellios Farmakides and Costas Giannouris received certificates 16092 and 16093.

The family pilgrimage

We now move many years forwards, to June 2013. A lady called Coralie Ganly, the daughter of the brave rear gunner Jack Ganley, living in Cairns, Australia, aware of the facts outlined above from correspondence between the family of pilot Peter Kennedy and Dr. Lambros in the eighties, found the ‘Friends of Diafani’ website. Some of you may have been familiar with this site, which was operated and updated on a regular basis by Margarita Dassas-Appleby, who lived in Paris and visited Diafani for prolonged periods for many years. note 4

Coralie had resolved to visit Karpathos with her partner Steve in October 2013. She approached Margarita after finding the site, explained her interest in finding out more and briefly outlined the background. She was aware that Dr Lambros was 75 in 1983 and had 4 daughters and a son, who had become a pharmacist. She had found a pharmacist in Karpathos called Lampros (the letters ‘b’ and ‘p’ are interchangeable on some occasions in Greek) and, wondering if this was the son, asked if more light could be shed.

With Margarita’s help and the cooperation of several others, a successful outcome resulted and I can do no better than quote Coralie’s email response to my request to pass all this on to you as a tale worth telling:

“Yes. We did meet Elias Lambros the pharmacist, his wife and two sisters and their families. They welcomed us with open arms and together with Margarita and Claude (Margarita’s spouse) they made our journey to Karpathos a very memorable experience. Our visit to Diafani was a highlight of my holiday because 1) I was able to visit the place where my father’s plane crashed 70 years ago and reflect on what he and his colleagues would have experienced as a result of the crash and 2) to pay tribute to Noel Fisher, his colleague who died. My partner Steve and I were overwhelmed by the warm gratitude expressed by the people of Diafani and Olympos. Thanks to Margarita I was able to meet with some of the men who, as little boys, witnessed the plane crash, and to meet the wonderful man who rowed out in a boat to rescue Dad and his wife. I never anticipated that I would be fortunate enough to meet these people and thank them for the kind and brave assistance they gave to my father and his colleagues.”

‘The wonderful man’, Kostas Lioreisis

© 2012 Manos Anastasiadis This ‘wonderful man’, then just a lad, now elderly gentleman, Kostas Lioreisis, remembers the rescue very well and has wondered all these years why there was so much paper floating all around them on the sea. Coralie surmised that this was maps relating to the reconnaissance they were engaged on which finally satisfied Kostas’ curiosity. Kostas had subsequently married Fotini who also has vivid memories of the rescue, the men having been housed in her aunt’s house where she took them such food as the villagers could spare. She also recalls that, despite being very wet and cold, the men were determined to maintain military dress and she helped to wash and dry their uniforms. As a couple they later opened a small hotel called ‘Diafani Palace’, which welcomed the first visitors to Diafani.

Coralie Ganly and Mr and Mrs Lioreisis

© Coralie Ganly Update June 2022 – “Secret Statement” surfaces

I completed this tale in 2013. It was sent to Coralie and the network of family and friends on my ‘mailing list’. And that was that. Then this website was created and the stories from Manolis Makris’ book ‘In the Years of the War’, together with this, were exposed to public view. Then naught else happened until in March 2021 when I learned that it had been translated into Greek and published in that week’s edition of ‘The Voice of Olympos’, a newspaper published and printed in Rhodes recounting events of interest to the people of Olympos and Diafani, accompanied by a flattering leader article!

Then, or now rather, Roger Jinkinson, the author of ‘Tales from Laos’ on this site, and the two volumes of stories, ‘Tales from a Greek Island’ and ‘More Tales from a Greek Island’, recounting characters and goings on in Diafani, sent me a document found by a friend of his in the UK National Archives at Kew, which is, in the context, stunning.

It is a ‘Secret Statement’ by A 414481, Warrant Officer John Archibald (Jack) Ganly, 454 squadron Bomber Command, RAF. himself! (Note: RAF! My title was wrong at the very start!) So, literally, straight from the horse’s mouth, I can do no better than quote it in full, with my notes where appropriate, (in brackets), to clarify. The text of the document below has been transcribed from the original held at the UK National Archives note 5 .

1. Evasion and capture

“I was the Wop/ag (wireless operator/gunner) of a Baltimore on a P.R. (photo reconnaissance) in the area of the Dodecanese on 21 Sep 43. We had just completed our recce of a harbour at the south end of the island of Skarpanto (This was the name the Italians gave Karpathos) and had gone about 25 miles up the East coast of the island when the port motor suddenly cut. We were at about 100 feet at the time and we immediately lost height, “bounced” on the sea and then banked steeply, and went into the water sideways. The aircraft sank instantly and when I came to I was under the water. I managed to get out through a crack in the rear of the fuselage. The Captain, W/O (Warrant Officer) Kennedy and navigator, W/O Lebich, had also managed to get out and we all got into the dinghy which had by this time floated free of the aircraft. The other Wop/ag, F/Sgt Fisher did not manage to get out and his body was later recovered by the Italian army personnel who came out for us. We were about 3-4 miles from the shore when we crashed and we could see boats putting out from the shore in our direction, so we sat in the dinghy and waited. It was by this time about 1130 hours. There were three boats in all manned by Italian soldiers and Greek civilians, and while one of the boats took us to the shore the others continued to search for Fisher’s body, which they found some time later. We tried artificial respiration and a doctor was fetched but he was beyond help.

“The doctor was Greek and was very helpful. We were able to converse with him through the medium of French and he spoke to the Italians on our behalf and they agreed not to hand us over to the Germans at Bagardia (the harbour town which we had reached) (Jack had misheard Pigadia, the capital of Karpathos). We were accommodated in the house of a Greek patriot and although food was very scarce they deprived themselves to feed us. Lebich had been severely injured in the crash and had lost a considerable amount of blood and the doctor visited him every day and did everything he could for him.

“Our plan was to procure a boat and endeavour to reach either Cos or Leros. But as Lebich was too weak to be moved we decided that only one of us should go and try to obtain help while the other would remain with our sick comrade.

“On the 26 Sep a Greek patriot arrived in a small boat. He had escaped from Crete and he agreed to take one of us to Leros. However, we were dissuaded by the Italians from making the trip as the boat was a very small one and they did not consider it safe for two passengers. However, they wrote a letter to the Commander of an Italian Garrison on a nearby island asking him to send a motor boat to take us off and our Greek boat owner agreed to deliver it.

“The following morning, however, we were surrounded by several Italian soldiers and it was obvious by their attitude that they had come for us. I managed to make a break and got some distance to the house of a Greek friend but was followed and captured.

“All three of us were then taken by small boat to Bagardia where we were turned over to the German garrison, the journey taking two days.”

2. Camps in which imprisoned

“In transit from Bagardia to Dulag Luft 27 Sep 43

“Dulag Luft. 1 Nov – 10 Nov 43

“Stalag IVB. Muhlberg. 11 Nov 43 – 23 Apr 45”

3. Attempted escapes

“Nil”

4. Liberation

“We were liberated by the Russians on 23 Apr 45”

———-

That’s it. Good to have another account and to know that they all three survived the war. Liberated on St George’s Day. For all who have come to know and love Karpathos, and particularly Diafani/Olympos as tourists, it beggars belief to stand in this beautiful place and conceive of these events. On reflection, I am writing this in my home in Bristol, where I spent lots of my childhood on bomb sites! Wars eh! What the hell are they for?

Epilogue

Please take a moment to pay tribute to all the men and women involved in these events, most of whom are no longer with us. Also, to pay tribute to that still-evident Greek impulse to assist those in need and to show courage in the face of adversity, as was demonstrated in 1943 and bas been reaffirmed during the recent difficult years.

I hope you agree that it is a heart-warming story and I take no credit for it other than assembling the pieces into as complete a picture as possible.

Bob Bowden

Footnote: To my surprise and delight this ‘snapshot’ has been translated into Greek and published in the March 2021 edition of the newspaper Η Φωνή της Ολύμπου (The Voice of Olympos). Read the ‘leader’ article which preceded it.

Leave a comment about this comment

Leave a comment about this comment

Article copyright ©2021 Bob Bowden.

454 Squadron RAAFYou can read more about the operations carried out by 454 Squadron in the book ‘Alamein to the Alps: 454 Squadron RAAF 1941-1945’ by Mark Lax. The book can be read online at www.yumpu.com.

Notes

Note 1: Source wikimedia.org https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:15_Martin_Baltimore_(15812407426).jpg. Uploaded to wikimedia by San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives. This image was taken from Flickr’s The Commons. The uploading organization may have various reasons for determining that no known copyright restrictions exist, such as: 1) The copyright is in the public domain because it has expired; 2) The copyright was injected into the public domain for other reasons, such as failure to adhere to required formalities or conditions; 3) The institution owns the copyright but is not interested in exercising control; or, 4) The institution has legal rights sufficient to authorize others to use the work without restrictions.

Return from Note 1

Note 2: The armistice of Cassibile represented a total capitulation of Italy to the Allies and was signed by King Victor Emanuel III and Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio following the Allies’ victories which had led to the surrender of 13th May 1943 of all Axis forces in North Africa, the Allied bombing of Rome on May 16th and the invasion of Sicily on July 10th with the threat of a landing on the mainland.

Return from Note 2

Note 3: The account does not make clear the nationality of these people.

Return from Note 3

Note 4: Sadly, Margarita passed away in 2014

Return from Note 4

Note 5: The text of the ‘Secret Statement’ has been transcribed from the record held at the UK National Archives. Use of the text is subject to the Open Government Licence.

Return from Note 5

With the help of the residents of Diafani, we held a funeral for Noel and buried him in the cemetery next to the little church of St Nicholas. We planted flowers around his grave and a small votive lamp was lit every night for his soul until September 30th when the Germans took over control of the island and to pay such respects to the memory of Noel would have been a very dangerous thing.

The Italian volta-face

A large boat arrived from Pighadia with a letter for the Italian non-commissioned officer in Diafani whose senior officer ordered him to hand over the Australian pilots DEAD OR ALIVE. The Italian ordered me to tell the survivors to come to his office as he had something urgent to announce.

Peter reacted furiously and told me to return the message that they would not go to his office, and if he had to tell them anything he should do so from the balcony so everyone could hear. So he came out onto the balcony and said he had received an order to hand the Allied troops over to the Germans. Peter shouted to him so that everyone could hear:

“Do you know that Italy has signed an armistice with the allies?” note 2

“Yes”, replied the Italian.

“Do you know that on the bottom of the armistice your king placed his signature?”

“Yes”, he replied once again.

“Do you know that from this moment on we are allies against the Germans?”

Again, “Yes.”

“Then, why are you handing us over to the Germans and violating your armistice?”

The Italian replied, “If anyone is violating the armistice, it is not I but my superior and I am obliged to carry out his orders.”

It was not possible to disagree with this argument so it was decided to surrender the airmen. We set off for the boat and somewhere along the beach front Liebeck said to me “Doctor, where was our comrade buried?” I showed him the church with the cemetery and all three stood silent on the beach with their head turned in the direction of their friend’s grave for a minute to bid him farewell. If they remember, they will recall that I wept like a child.

The botched rescue

It should also be remembered that we sent a man in a small boat to Symi, where the English already were, to inform them of what had happened in Diafani and to ask them to come and rescue our companions. Four or five days had already passed and we had heard nothing. But we hoped from hour to hour that help would arrive so we told the captain of the boat that we needed to call in at a small harbour and contact the village doctor so that he could come and change the dressings of the wounded. This was not necessary but we were trying to delay our arrival in Pighadia where the Germans were waiting.

We delayed the boat, and the doctor came and changed the dressings, but we were then obliged to set off for Pighadia where we arrived late in the afternoon and they were handed over to the Germans by ‘these Italian pigs’ as Peter called them.

That same night a British commando arrived in Diafani but was forced to hide until daybreak because the Italians were celebrating the armistice by throwing grenades and he thought that some sort of combat was taking place!

Early next morning two soldiers, armed to the teeth, and a civilian came and asked the Italians where the pilots were. note 3 The Italians replied that the Germans had them and at the mention of the word ‘Germans’, without asking how, when, why or where, they ran to the beach as if being shot at! In their haste, and not listening to our advice not to run because the Germans were 50 kilometres away, they took a boat and set off for the boat that had brought them. But the boat leaked and 500 metres from Diafani, it sank. One soldier took off his weapons and the civilian his overcoat and managed to swim to their boat but the other soldier was not so fortunate and drowned. His companions, intent only on getting away, left – and are probably still going!

We saw what had happened and quickly took a boat to the scene of the tragedy, where, after an hour’s searching, we found the body. We brought him back, laid him on the sand and gave artificial respiration and heart massage but without success. We buried him next to Joel.

So, you can see that the delay in arrival of commandoes was fatal and led to the imprisonment of Peter, Alvin and Jack. If they had arrived in time and saved the pilots, they would have continued in the war, if not in the Mediterranean, then elsewhere and, who knows, may have been killed fighting. Their subsequent imprisonment was bitter and their future uncertain but they were fortunate enough to be sent to a prisoner-of-war camp and survived intact to be freed by the Russian invasion of Germany.

After the war

The gratitude of Great Britain and the Commonwealth

Returning home, they paused in London and went to the Air Ministry to relate the assistance they had received in Diafani. Months later I received a parcel from Australia containing sugar, coffee, butter, cheese, corned beef and a clock with the inscription ‘To Doctor Andreas Lambros from Alvin Liebeck for September 1943’.

In July 1946 an English ship arrived in Pighadia and I was sought out. I was taken to a major who spoke good Greek, a lieutenant and a secretary in civilian clothes. The major asked me my name and if during the war I had helped Australian pilots. I told him my name and the help I gave in 1943 and that I had received a letter from Liebick and that if he wanted I could bring it from my surgery. “No”, he said, “we know everything, so the reason we came here is to pay you, Doctor, for everything you did for our pilots and for anyone else you helped because we will never pass this way again.”

I asked the major to translate what he had said for the lieutenant to hear. I then said “I only did my duty as a patriotic Greek doctor just as anyone else in the same position would have done. I do not want any money. I am only sorry that when war broke out, I was not in Greece to fight the Italians in Albania and then Greece fell, not to the Italians but the Germans, I wanted to be in Crete and when Crete fell, I wanted to be in Egypt and, if God had given me time, I would have liked to have marched through Rome and Berlin. That I did my duty and would not accept any money.”

The major, on hearing my words, arose and approached me with tears in his eyes. “What are you Greeks?! Three thousand years have passed since the battle of Marathon and the same blood flows through your veins!”

“Doctor, I have been ordered by Field-Marshal Alexander, to give you the certificate in which is expressed the gratitude and honour of Great Britain and the Commonwealth for everything you did during the war of 1939-1945.”

This I accepted and it is now on my surgery wall, numbered 16091 to remind me always of a good patriotic example. Two other colleagues, Stellios Farmakides and Costas Giannouris received certificates 16092 and 16093.

The family pilgrimage

We now move many years forwards, to June 2013. A lady called Coralie Ganly, the daughter of the brave rear gunner Jack Ganley, living in Cairns, Australia, aware of the facts outlined above from correspondence between the family of pilot Peter Kennedy and Dr. Lambros in the eighties, found the ‘Friends of Diafani’ website. Some of you may have been familiar with this site, which was operated and updated on a regular basis by Margarita Dassas-Appleby, who lived in Paris and visited Diafani for prolonged periods for many years. note 4

Coralie had resolved to visit Karpathos with her partner Steve in October 2013. She approached Margarita after finding the site, explained her interest in finding out more and briefly outlined the background. She was aware that Dr Lambros was 75 in 1983 and had 4 daughters and a son, who had become a pharmacist. She had found a pharmacist in Karpathos called Lampros (the letters ‘b’ and ‘p’ are interchangeable on some occasions in Greek) and, wondering if this was the son, asked if more light could be shed.

With Margarita’s help and the cooperation of several others, a successful outcome resulted and I can do no better than quote Coralie’s email response to my request to pass all this on to you as a tale worth telling:

“Yes. We did meet Elias Lambros the pharmacist, his wife and two sisters and their families. They welcomed us with open arms and together with Margarita and Claude (Margarita’s spouse) they made our journey to Karpathos a very memorable experience. Our visit to Diafani was a highlight of my holiday because 1) I was able to visit the place where my father’s plane crashed 70 years ago and reflect on what he and his colleagues would have experienced as a result of the crash and 2) to pay tribute to Noel Fisher, his colleague who died. My partner Steve and I were overwhelmed by the warm gratitude expressed by the people of Diafani and Olympos. Thanks to Margarita I was able to meet with some of the men who, as little boys, witnessed the plane crash, and to meet the wonderful man who rowed out in a boat to rescue Dad and his wife. I never anticipated that I would be fortunate enough to meet these people and thank them for the kind and brave assistance they gave to my father and his colleagues.”

‘The wonderful man’, Kostas Lioreisis

© 2012 Manos Anastasiadis This ‘wonderful man’, then just a lad, now elderly gentleman, Kostas Lioreisis, remembers the rescue very well and has wondered all these years why there was so much paper floating all around them on the sea. Coralie surmised that this was maps relating to the reconnaissance they were engaged on which finally satisfied Kostas’ curiosity. Kostas had subsequently married Fotini who also has vivid memories of the rescue, the men having been housed in her aunt’s house where she took them such food as the villagers could spare. She also recalls that, despite being very wet and cold, the men were determined to maintain military dress and she helped to wash and dry their uniforms. As a couple they later opened a small hotel called ‘Diafani Palace’, which welcomed the first visitors to Diafani.

Coralie Ganly and Mr and Mrs Lioreisis

© Coralie Ganly Update June 2022 – “Secret Statement” surfaces

I completed this tale in 2013. It was sent to Coralie and the network of family and friends on my ‘mailing list’. And that was that. Then this website was created and the stories from Manolis Makris’ book ‘In the Years of the War’, together with this, were exposed to public view. Then naught else happened until in March 2021 when I learned that it had been translated into Greek and published in that week’s edition of ‘The Voice of Olympos’, a newspaper published and printed in Rhodes recounting events of interest to the people of Olympos and Diafani, accompanied by a flattering leader article!

Then, or now rather, Roger Jinkinson, the author of ‘Tales from Laos’ on this site, and the two volumes of stories, ‘Tales from a Greek Island’ and ‘More Tales from a Greek Island’, recounting characters and goings on in Diafani, sent me a document found by a friend of his in the UK National Archives at Kew, which is, in the context, stunning.

It is a ‘Secret Statement’ by A 414481, Warrant Officer John Archibald (Jack) Ganly, 454 squadron Bomber Command, RAF. himself! (Note: RAF! My title was wrong at the very start!) So, literally, straight from the horse’s mouth, I can do no better than quote it in full, with my notes where appropriate, (in brackets), to clarify. The text of the document below has been transcribed from the original held at the UK National Archives note 5 .

1. Evasion and capture

“I was the Wop/ag (wireless operator/gunner) of a Baltimore on a P.R. (photo reconnaissance) in the area of the Dodecanese on 21 Sep 43. We had just completed our recce of a harbour at the south end of the island of Skarpanto (This was the name the Italians gave Karpathos) and had gone about 25 miles up the East coast of the island when the port motor suddenly cut. We were at about 100 feet at the time and we immediately lost height, “bounced” on the sea and then banked steeply, and went into the water sideways. The aircraft sank instantly and when I came to I was under the water. I managed to get out through a crack in the rear of the fuselage. The Captain, W/O (Warrant Officer) Kennedy and navigator, W/O Lebich, had also managed to get out and we all got into the dinghy which had by this time floated free of the aircraft. The other Wop/ag, F/Sgt Fisher did not manage to get out and his body was later recovered by the Italian army personnel who came out for us. We were about 3-4 miles from the shore when we crashed and we could see boats putting out from the shore in our direction, so we sat in the dinghy and waited. It was by this time about 1130 hours. There were three boats in all manned by Italian soldiers and Greek civilians, and while one of the boats took us to the shore the others continued to search for Fisher’s body, which they found some time later. We tried artificial respiration and a doctor was fetched but he was beyond help.

“The doctor was Greek and was very helpful. We were able to converse with him through the medium of French and he spoke to the Italians on our behalf and they agreed not to hand us over to the Germans at Bagardia (the harbour town which we had reached) (Jack had misheard Pigadia, the capital of Karpathos). We were accommodated in the house of a Greek patriot and although food was very scarce they deprived themselves to feed us. Lebich had been severely injured in the crash and had lost a considerable amount of blood and the doctor visited him every day and did everything he could for him.

“Our plan was to procure a boat and endeavour to reach either Cos or Leros. But as Lebich was too weak to be moved we decided that only one of us should go and try to obtain help while the other would remain with our sick comrade.

“On the 26 Sep a Greek patriot arrived in a small boat. He had escaped from Crete and he agreed to take one of us to Leros. However, we were dissuaded by the Italians from making the trip as the boat was a very small one and they did not consider it safe for two passengers. However, they wrote a letter to the Commander of an Italian Garrison on a nearby island asking him to send a motor boat to take us off and our Greek boat owner agreed to deliver it.

“The following morning, however, we were surrounded by several Italian soldiers and it was obvious by their attitude that they had come for us. I managed to make a break and got some distance to the house of a Greek friend but was followed and captured.

“All three of us were then taken by small boat to Bagardia where we were turned over to the German garrison, the journey taking two days.”

2. Camps in which imprisoned

“In transit from Bagardia to Dulag Luft 27 Sep 43

“Dulag Luft. 1 Nov – 10 Nov 43

“Stalag IVB. Muhlberg. 11 Nov 43 – 23 Apr 45”

3. Attempted escapes

“Nil”

4. Liberation

“We were liberated by the Russians on 23 Apr 45”

———-

That’s it. Good to have another account and to know that they all three survived the war. Liberated on St George’s Day. For all who have come to know and love Karpathos, and particularly Diafani/Olympos as tourists, it beggars belief to stand in this beautiful place and conceive of these events. On reflection, I am writing this in my home in Bristol, where I spent lots of my childhood on bomb sites! Wars eh! What the hell are they for?

Epilogue

Please take a moment to pay tribute to all the men and women involved in these events, most of whom are no longer with us. Also, to pay tribute to that still-evident Greek impulse to assist those in need and to show courage in the face of adversity, as was demonstrated in 1943 and bas been reaffirmed during the recent difficult years.

I hope you agree that it is a heart-warming story and I take no credit for it other than assembling the pieces into as complete a picture as possible.

Bob Bowden

Footnote: To my surprise and delight this ‘snapshot’ has been translated into Greek and published in the March 2021 edition of the newspaper Η Φωνή της Ολύμπου (The Voice of Olympos). Read the ‘leader’ article which preceded it.

Leave a comment about this comment

Leave a comment about this comment

Article copyright ©2021 Bob Bowden.

454 Squadron RAAFYou can read more about the operations carried out by 454 Squadron in the book ‘Alamein to the Alps: 454 Squadron RAAF 1941-1945’ by Mark Lax. The book can be read online at www.yumpu.com.

Notes

Note 1: Source wikimedia.org https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:15_Martin_Baltimore_(15812407426).jpg. Uploaded to wikimedia by San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives. This image was taken from Flickr’s The Commons. The uploading organization may have various reasons for determining that no known copyright restrictions exist, such as: 1) The copyright is in the public domain because it has expired; 2) The copyright was injected into the public domain for other reasons, such as failure to adhere to required formalities or conditions; 3) The institution owns the copyright but is not interested in exercising control; or, 4) The institution has legal rights sufficient to authorize others to use the work without restrictions.

Return from Note 1

Note 2: The armistice of Cassibile represented a total capitulation of Italy to the Allies and was signed by King Victor Emanuel III and Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio following the Allies’ victories which had led to the surrender of 13th May 1943 of all Axis forces in North Africa, the Allied bombing of Rome on May 16th and the invasion of Sicily on July 10th with the threat of a landing on the mainland.

Return from Note 2

Note 3: The account does not make clear the nationality of these people.

Return from Note 3

Note 4: Sadly, Margarita passed away in 2014

Return from Note 4

Note 5: The text of the ‘Secret Statement’ has been transcribed from the record held at the UK National Archives. Use of the text is subject to the Open Government Licence.

Return from Note 5

The gratitude of Great Britain and the Commonwealth

Returning home, they paused in London and went to the Air Ministry to relate the assistance they had received in Diafani. Months later I received a parcel from Australia containing sugar, coffee, butter, cheese, corned beef and a clock with the inscription ‘To Doctor Andreas Lambros from Alvin Liebeck for September 1943’.

In July 1946 an English ship arrived in Pighadia and I was sought out. I was taken to a major who spoke good Greek, a lieutenant and a secretary in civilian clothes. The major asked me my name and if during the war I had helped Australian pilots. I told him my name and the help I gave in 1943 and that I had received a letter from Liebick and that if he wanted I could bring it from my surgery. “No”, he said, “we know everything, so the reason we came here is to pay you, Doctor, for everything you did for our pilots and for anyone else you helped because we will never pass this way again.”

I asked the major to translate what he had said for the lieutenant to hear. I then said “I only did my duty as a patriotic Greek doctor just as anyone else in the same position would have done. I do not want any money. I am only sorry that when war broke out, I was not in Greece to fight the Italians in Albania and then Greece fell, not to the Italians but the Germans, I wanted to be in Crete and when Crete fell, I wanted to be in Egypt and, if God had given me time, I would have liked to have marched through Rome and Berlin. That I did my duty and would not accept any money.”

The major, on hearing my words, arose and approached me with tears in his eyes. “What are you Greeks?! Three thousand years have passed since the battle of Marathon and the same blood flows through your veins!”

“Doctor, I have been ordered by Field-Marshal Alexander, to give you the certificate in which is expressed the gratitude and honour of Great Britain and the Commonwealth for everything you did during the war of 1939-1945.”

This I accepted and it is now on my surgery wall, numbered 16091 to remind me always of a good patriotic example. Two other colleagues, Stellios Farmakides and Costas Giannouris received certificates 16092 and 16093.

The family pilgrimage

We now move many years forwards, to June 2013. A lady called Coralie Ganly, the daughter of the brave rear gunner Jack Ganley, living in Cairns, Australia, aware of the facts outlined above from correspondence between the family of pilot Peter Kennedy and Dr. Lambros in the eighties, found the ‘Friends of Diafani’ website. Some of you may have been familiar with this site, which was operated and updated on a regular basis by Margarita Dassas-Appleby, who lived in Paris and visited Diafani for prolonged periods for many years. note 4

Coralie had resolved to visit Karpathos with her partner Steve in October 2013. She approached Margarita after finding the site, explained her interest in finding out more and briefly outlined the background. She was aware that Dr Lambros was 75 in 1983 and had 4 daughters and a son, who had become a pharmacist. She had found a pharmacist in Karpathos called Lampros (the letters ‘b’ and ‘p’ are interchangeable on some occasions in Greek) and, wondering if this was the son, asked if more light could be shed.

With Margarita’s help and the cooperation of several others, a successful outcome resulted and I can do no better than quote Coralie’s email response to my request to pass all this on to you as a tale worth telling:

“Yes. We did meet Elias Lambros the pharmacist, his wife and two sisters and their families. They welcomed us with open arms and together with Margarita and Claude (Margarita’s spouse) they made our journey to Karpathos a very memorable experience. Our visit to Diafani was a highlight of my holiday because 1) I was able to visit the place where my father’s plane crashed 70 years ago and reflect on what he and his colleagues would have experienced as a result of the crash and 2) to pay tribute to Noel Fisher, his colleague who died. My partner Steve and I were overwhelmed by the warm gratitude expressed by the people of Diafani and Olympos. Thanks to Margarita I was able to meet with some of the men who, as little boys, witnessed the plane crash, and to meet the wonderful man who rowed out in a boat to rescue Dad and his wife. I never anticipated that I would be fortunate enough to meet these people and thank them for the kind and brave assistance they gave to my father and his colleagues.”

© 2012 Manos Anastasiadis

This ‘wonderful man’, then just a lad, now elderly gentleman, Kostas Lioreisis, remembers the rescue very well and has wondered all these years why there was so much paper floating all around them on the sea. Coralie surmised that this was maps relating to the reconnaissance they were engaged on which finally satisfied Kostas’ curiosity. Kostas had subsequently married Fotini who also has vivid memories of the rescue, the men having been housed in her aunt’s house where she took them such food as the villagers could spare. She also recalls that, despite being very wet and cold, the men were determined to maintain military dress and she helped to wash and dry their uniforms. As a couple they later opened a small hotel called ‘Diafani Palace’, which welcomed the first visitors to Diafani.

© Coralie Ganly

Update June 2022 – “Secret Statement” surfaces

I completed this tale in 2013. It was sent to Coralie and the network of family and friends on my ‘mailing list’. And that was that. Then this website was created and the stories from Manolis Makris’ book ‘In the Years of the War’, together with this, were exposed to public view. Then naught else happened until in March 2021 when I learned that it had been translated into Greek and published in that week’s edition of ‘The Voice of Olympos’, a newspaper published and printed in Rhodes recounting events of interest to the people of Olympos and Diafani, accompanied by a flattering leader article!

Then, or now rather, Roger Jinkinson, the author of ‘Tales from Laos’ on this site, and the two volumes of stories, ‘Tales from a Greek Island’ and ‘More Tales from a Greek Island’, recounting characters and goings on in Diafani, sent me a document found by a friend of his in the UK National Archives at Kew, which is, in the context, stunning.

It is a ‘Secret Statement’ by A 414481, Warrant Officer John Archibald (Jack) Ganly, 454 squadron Bomber Command, RAF. himself! (Note: RAF! My title was wrong at the very start!) So, literally, straight from the horse’s mouth, I can do no better than quote it in full, with my notes where appropriate, (in brackets), to clarify. The text of the document below has been transcribed from the original held at the UK National Archives note 5 .

1. Evasion and capture

“I was the Wop/ag (wireless operator/gunner) of a Baltimore on a P.R. (photo reconnaissance) in the area of the Dodecanese on 21 Sep 43. We had just completed our recce of a harbour at the south end of the island of Skarpanto (This was the name the Italians gave Karpathos) and had gone about 25 miles up the East coast of the island when the port motor suddenly cut. We were at about 100 feet at the time and we immediately lost height, “bounced” on the sea and then banked steeply, and went into the water sideways. The aircraft sank instantly and when I came to I was under the water. I managed to get out through a crack in the rear of the fuselage. The Captain, W/O (Warrant Officer) Kennedy and navigator, W/O Lebich, had also managed to get out and we all got into the dinghy which had by this time floated free of the aircraft. The other Wop/ag, F/Sgt Fisher did not manage to get out and his body was later recovered by the Italian army personnel who came out for us. We were about 3-4 miles from the shore when we crashed and we could see boats putting out from the shore in our direction, so we sat in the dinghy and waited. It was by this time about 1130 hours. There were three boats in all manned by Italian soldiers and Greek civilians, and while one of the boats took us to the shore the others continued to search for Fisher’s body, which they found some time later. We tried artificial respiration and a doctor was fetched but he was beyond help.

“The doctor was Greek and was very helpful. We were able to converse with him through the medium of French and he spoke to the Italians on our behalf and they agreed not to hand us over to the Germans at Bagardia (the harbour town which we had reached) (Jack had misheard Pigadia, the capital of Karpathos). We were accommodated in the house of a Greek patriot and although food was very scarce they deprived themselves to feed us. Lebich had been severely injured in the crash and had lost a considerable amount of blood and the doctor visited him every day and did everything he could for him.

“Our plan was to procure a boat and endeavour to reach either Cos or Leros. But as Lebich was too weak to be moved we decided that only one of us should go and try to obtain help while the other would remain with our sick comrade.

“On the 26 Sep a Greek patriot arrived in a small boat. He had escaped from Crete and he agreed to take one of us to Leros. However, we were dissuaded by the Italians from making the trip as the boat was a very small one and they did not consider it safe for two passengers. However, they wrote a letter to the Commander of an Italian Garrison on a nearby island asking him to send a motor boat to take us off and our Greek boat owner agreed to deliver it.

“The following morning, however, we were surrounded by several Italian soldiers and it was obvious by their attitude that they had come for us. I managed to make a break and got some distance to the house of a Greek friend but was followed and captured.

“All three of us were then taken by small boat to Bagardia where we were turned over to the German garrison, the journey taking two days.”

2. Camps in which imprisoned

“In transit from Bagardia to Dulag Luft 27 Sep 43

“Dulag Luft. 1 Nov – 10 Nov 43

“Stalag IVB. Muhlberg. 11 Nov 43 – 23 Apr 45”

3. Attempted escapes

“Nil”

4. Liberation

“We were liberated by the Russians on 23 Apr 45”

———-

That’s it. Good to have another account and to know that they all three survived the war. Liberated on St George’s Day. For all who have come to know and love Karpathos, and particularly Diafani/Olympos as tourists, it beggars belief to stand in this beautiful place and conceive of these events. On reflection, I am writing this in my home in Bristol, where I spent lots of my childhood on bomb sites! Wars eh! What the hell are they for?

Epilogue

Please take a moment to pay tribute to all the men and women involved in these events, most of whom are no longer with us. Also, to pay tribute to that still-evident Greek impulse to assist those in need and to show courage in the face of adversity, as was demonstrated in 1943 and bas been reaffirmed during the recent difficult years.

I hope you agree that it is a heart-warming story and I take no credit for it other than assembling the pieces into as complete a picture as possible.

Bob Bowden

Footnote: To my surprise and delight this ‘snapshot’ has been translated into Greek and published in the March 2021 edition of the newspaper Η Φωνή της Ολύμπου (The Voice of Olympos). Read the ‘leader’ article which preceded it.

Leave a comment about this comment

Leave a comment about this comment

Article copyright ©2021 Bob Bowden.

454 Squadron RAAFYou can read more about the operations carried out by 454 Squadron in the book ‘Alamein to the Alps: 454 Squadron RAAF 1941-1945’ by Mark Lax. The book can be read online at www.yumpu.com.

Notes

Note 1: Source wikimedia.org https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:15_Martin_Baltimore_(15812407426).jpg. Uploaded to wikimedia by San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives. This image was taken from Flickr’s The Commons. The uploading organization may have various reasons for determining that no known copyright restrictions exist, such as: 1) The copyright is in the public domain because it has expired; 2) The copyright was injected into the public domain for other reasons, such as failure to adhere to required formalities or conditions; 3) The institution owns the copyright but is not interested in exercising control; or, 4) The institution has legal rights sufficient to authorize others to use the work without restrictions.

Return from Note 1

Note 2: The armistice of Cassibile represented a total capitulation of Italy to the Allies and was signed by King Victor Emanuel III and Prime Minister Pietro Badoglio following the Allies’ victories which had led to the surrender of 13th May 1943 of all Axis forces in North Africa, the Allied bombing of Rome on May 16th and the invasion of Sicily on July 10th with the threat of a landing on the mainland.

Return from Note 2

Note 3: The account does not make clear the nationality of these people.

Return from Note 3

Note 4: Sadly, Margarita passed away in 2014

Return from Note 4

Note 5: The text of the ‘Secret Statement’ has been transcribed from the record held at the UK National Archives. Use of the text is subject to the Open Government Licence.

Return from Note 5

I completed this tale in 2013. It was sent to Coralie and the network of family and friends on my ‘mailing list’. And that was that. Then this website was created and the stories from Manolis Makris’ book ‘In the Years of the War’, together with this, were exposed to public view. Then naught else happened until in March 2021 when I learned that it had been translated into Greek and published in that week’s edition of ‘The Voice of Olympos’, a newspaper published and printed in Rhodes recounting events of interest to the people of Olympos and Diafani, accompanied by a flattering leader article!

Then, or now rather, Roger Jinkinson, the author of ‘Tales from Laos’ on this site, and the two volumes of stories, ‘Tales from a Greek Island’ and ‘More Tales from a Greek Island’, recounting characters and goings on in Diafani, sent me a document found by a friend of his in the UK National Archives at Kew, which is, in the context, stunning.

It is a ‘Secret Statement’ by A 414481, Warrant Officer John Archibald (Jack) Ganly, 454 squadron Bomber Command, RAF. himself! (Note: RAF! My title was wrong at the very start!) So, literally, straight from the horse’s mouth, I can do no better than quote it in full, with my notes where appropriate, (in brackets), to clarify. The text of the document below has been transcribed from the original held at the UK National Archives note 5 .

1. Evasion and capture

“I was the Wop/ag (wireless operator/gunner) of a Baltimore on a P.R. (photo reconnaissance) in the area of the Dodecanese on 21 Sep 43. We had just completed our recce of a harbour at the south end of the island of Skarpanto (This was the name the Italians gave Karpathos) and had gone about 25 miles up the East coast of the island when the port motor suddenly cut. We were at about 100 feet at the time and we immediately lost height, “bounced” on the sea and then banked steeply, and went into the water sideways. The aircraft sank instantly and when I came to I was under the water. I managed to get out through a crack in the rear of the fuselage. The Captain, W/O (Warrant Officer) Kennedy and navigator, W/O Lebich, had also managed to get out and we all got into the dinghy which had by this time floated free of the aircraft. The other Wop/ag, F/Sgt Fisher did not manage to get out and his body was later recovered by the Italian army personnel who came out for us. We were about 3-4 miles from the shore when we crashed and we could see boats putting out from the shore in our direction, so we sat in the dinghy and waited. It was by this time about 1130 hours. There were three boats in all manned by Italian soldiers and Greek civilians, and while one of the boats took us to the shore the others continued to search for Fisher’s body, which they found some time later. We tried artificial respiration and a doctor was fetched but he was beyond help.

“The doctor was Greek and was very helpful. We were able to converse with him through the medium of French and he spoke to the Italians on our behalf and they agreed not to hand us over to the Germans at Bagardia (the harbour town which we had reached) (Jack had misheard Pigadia, the capital of Karpathos). We were accommodated in the house of a Greek patriot and although food was very scarce they deprived themselves to feed us. Lebich had been severely injured in the crash and had lost a considerable amount of blood and the doctor visited him every day and did everything he could for him.

“Our plan was to procure a boat and endeavour to reach either Cos or Leros. But as Lebich was too weak to be moved we decided that only one of us should go and try to obtain help while the other would remain with our sick comrade.

“On the 26 Sep a Greek patriot arrived in a small boat. He had escaped from Crete and he agreed to take one of us to Leros. However, we were dissuaded by the Italians from making the trip as the boat was a very small one and they did not consider it safe for two passengers. However, they wrote a letter to the Commander of an Italian Garrison on a nearby island asking him to send a motor boat to take us off and our Greek boat owner agreed to deliver it.

“The following morning, however, we were surrounded by several Italian soldiers and it was obvious by their attitude that they had come for us. I managed to make a break and got some distance to the house of a Greek friend but was followed and captured.

“All three of us were then taken by small boat to Bagardia where we were turned over to the German garrison, the journey taking two days.”

2. Camps in which imprisoned

“In transit from Bagardia to Dulag Luft 27 Sep 43

“Dulag Luft. 1 Nov – 10 Nov 43

“Stalag IVB. Muhlberg. 11 Nov 43 – 23 Apr 45”

3. Attempted escapes

“Nil”

4. Liberation

“We were liberated by the Russians on 23 Apr 45”

———-

That’s it. Good to have another account and to know that they all three survived the war. Liberated on St George’s Day. For all who have come to know and love Karpathos, and particularly Diafani/Olympos as tourists, it beggars belief to stand in this beautiful place and conceive of these events. On reflection, I am writing this in my home in Bristol, where I spent lots of my childhood on bomb sites! Wars eh! What the hell are they for?

Epilogue

Please take a moment to pay tribute to all the men and women involved in these events, most of whom are no longer with us. Also, to pay tribute to that still-evident Greek impulse to assist those in need and to show courage in the face of adversity, as was demonstrated in 1943 and bas been reaffirmed during the recent difficult years.

I hope you agree that it is a heart-warming story and I take no credit for it other than assembling the pieces into as complete a picture as possible.

Bob Bowden

Footnote: To my surprise and delight this ‘snapshot’ has been translated into Greek and published in the March 2021 edition of the newspaper Η Φωνή της Ολύμπου (The Voice of Olympos). Read the ‘leader’ article which preceded it.

Leave a comment about this comment

Leave a comment about this comment

Article copyright ©2021 Bob Bowden.

454 Squadron RAAFYou can read more about the operations carried out by 454 Squadron in the book ‘Alamein to the Alps: 454 Squadron RAAF 1941-1945’ by Mark Lax. The book can be read online at www.yumpu.com.

Notes