The true story of an aristocratic British archaeologist and his profound love for the Greek goddess he encountered on the remote Greek island of Kalymnos.

- Love at first sight

- Theodore and Mabel Bent visit Kalymnos

- Return to Scotland

- The house by the Aegean Sea

- Paris

- Brittany

- A sad, sad ending

Love at first sight

William Roger Paton was born in Scotland on September 2nd 1857. He studied Classics at Oxford and London and moved on to law for a while in London. However, the legal world was clearly too staid for William, whose real interests lay further afield in literature and archaeology in the Eastern Mediterranean. One wonders whether Oscar Wilde had his friend William Paton in mind when he wrote “To live is the rarest thing in the world. Most people exist, that is all.”

On one of his trips to the region in the late summer of 1885, his ship anchored off-shore near the port village of Pothia on the Turkish-controlled Greek island of Kalymnos. Standing on the deck of the steamer, he could not have known that his life was about to take a turn which would see him married within just 3 months and a father before a year had passed.

Few large ships called at Kalymnos in those days; there was no dock and such ships had to anchor well out to sea. As soon as a ship was spotted, a scramble of small boats would go out to meet it to take off alighting passengers and maybe to make a few piastre from the ship’s passengers. The local boys would hope to come back with a coin or two by entertaining the passengers with their diving skills as they retrieved coins thrown from the deck.

Leaning on the rail, Paton’s eyes were intractably drawn to one of the small boats. In it sat the young girl who would become his wife and the mother of his four children. His fate was sealed at that very moment in time.

He instantly made up his mind. Quickly getting his baggage together, he disembarked into one of the small boats. To the surprise of the boatman, in perfect Greek, he asked where he could find accommodation on the island. The boatman agreed to take ‘O Lordos’ note 1 to the most important man on the island, the Demarchos, or Mayor. As he rowed toward the shore, singing the praises of the Demarchos, he added, with a nod of his head toward the boat which had so captivated Paton, “that young girl is his daughter.”

Paton got on well with the Demarchos, Emmanouil Olympitis, who very much impressed the younger Paton. He was successful in the sponge fishing industry, for which Kalymnos has always been renowned, and the family was much respected by the people of Kalymnos for the defiance that Emmanouil’s grandfather had shown toward the occupying Turks.

However well the two men got on, it must have been a bolt out of the blue the very next day when Paton proposed marriage to his daughter, Irini. People were outraged and, on a more lawless island, this might have been the end of Paton’s amorous advances, and his life to boot! But wise Emmanouil Olympitis was far above all that and countered by trying to delay on the basis that a trousseau needed to be arranged. With dogged persistence, Paton told him he would arrange everything and that he wanted Irini just as she was.

And what of Irini’s feelings in all of this? Of course, Emmanouil Olympitis would not have allowed his daughter to enter into marriage against her will. We learn from the autobiography of Irini’s daughter, Augusta, from later conversations with her mother, that Paton’s emotions were mirrored in Irini’s own; she described him as a ‘fair, blue-eyed god’.

Paton stayed in Kalymnos for a month and he and Irini grew ever closer – but he had to return to Britain leaving Irini in Kalymnos. While in Britain, he wrote her long letters every single day.

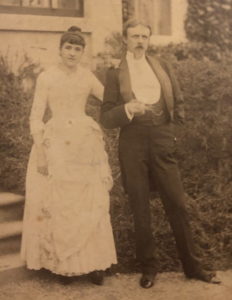

On Paton’s return to Kalymnos, two months later, signalled by tender telegram messages to Irini from each port of call along the way, they married in November 1885 – he 28 and Irini 16 years of age.

Shortly after their marriage and their honeymoon in Symi and Rhodes, they moved to Paton’s Scottish estate, but neither Paton nor Irini were happy in Scotland and both pined for Greece. From Mabel Bent’s diary entry, we know they were back in Kalymnos by March 1886. Later that year, in August, their first son George was born in Irini’s mother’s house on the Turkish coast at Gümüşlük near Bodrum.

Theodore and Mabel Bent visit Kalymnos

At the beginning of 1886, the British explorers Theodore and Mabel Bent were travelling around the islands of the eastern Aegean looking for potential archaeological sites to excavate.

Bent and Paton were acquainted. It’s thought that they first met as a result of their connections with the British Museum or as members of the Hellenic Society. Their various papers on their respective archaeological excavations were published by the same journal, sometimes in the same issue. They would have been very well aware of each other’s work.

However, it seems that it was actually Mabel Bent’s inquisitiveness which drove their decision to visit Kalymnos. She wrote in her diary:

“I am most curious to see a young lady of Kalymnos, aged I hear about 16 and just married to a Mr. William Paton of Granholme in Aberdeenshire. Her father’s name is Olympites, a sponge merchant and very rich. Everyone has heard of ‘O Ouiliermos’ note 2 in the neighbouring islands.”

They arrived in Kalymnos on Wednesday March 17th, 1886. The next day Mabel wrote:

“We were lucky enough to fall in with a clean little English steamer, lanthe, where we had a most comfortable flealess night and a very calm passage here. We started about 6 and arrived about ½ past 12 yesterday.

This is a very populous town of large houses filled with rich sponge fishers who have a reputation in these regions of being thieves, liars and cheats. We were sorry to hear that Mr. Paton had returned to England 2 days ago, leaving his wife at her father’s as she does not wish to undertake the long journey till the summer of next year.”

So the Bents missed meeting Paton in Kalymnos. Whether Bent and Paton ever met on their overseas travels we don’t know – but they certainly trod in each other’s footsteps.

It would seem that they had more than just a passing physical resemblance to each other. On Kalymnos, this created some confusion on the island:

“We were very much amused on landing to hear William has returned’. ‘No, it is his brother.’ ‘He is exactly the same.’ ‘How very like he is.’ ‘No, it is not him.’ And these sentences never cease to be buzzed round wherever Theodore goes. At the British Museum they have been taken for one another and a gentleman came and shook hands with him and said ‘When did you come’ and then ‘Oh! Excuse me. I thought you were the son-in-law of Olympidis’.”

Meeting Irini’s father Emmanouil Olympitis

But one man, at least, was not fooled by Bent’s apparent likeness to Paton. He approached Theodore, saying in English:

‘This is the father-in-law of Mr. Paton and I am the brother-in-law of Mrs. Paton.’

Thus were the Bents introduced to Emmanouil Olympitis, the Demarchos of Kalymnos and the father of Irini, Paton’s wife. Mabel continues:

“So on invitation we entered the café and gave our history, in Greek, to the crowd. The brother asked us to come and take a walk in their garden, so we were removed to an orchard of young lemon and orange trees. Chairs were procured and we sat on ploughed beds, damp, so that one had never to forget to be always trying to sit on the highest leg of the chair for fear of overturning. He would talk English which we had constantly to help out with Greek so we sat silently for a long time till I shivered loudly and we were led silently home.”

Meeting Mrs Irini Paton

Mabel continues, but it should be stressed that she is a product of the Victorian era; she is writing her diary for herself and a small number of friends and family, and, as such, her tone sometimes borders on the xenophobic, the insensitive and the rude:

“We announced that in an hour we would call on Mrs. Paton. Accordingly they prepared themselves. We entered a mud-floored hall littered with broken machinery; up dirty marble stairs with a rusty banister and reached a drawing room where some matting had been thrown down, but rolled up where it could not pass under the chest of drawers. A quantity of pieces of embroidery bought during the honeymoon to Simi and Rhodes were plastered round in an absurd way. The chest of drawers had a green table cover falling over the front of it, over that a large cotton antimacassar and on top a large pier glass smashed in 4 bits, some hanging out.

Mrs. Paton is a fine big girl who might pass for 20 but some say 14. She had a pretty new dress, quite out of keeping with the place, her wedding ring and a splendid diamond one on her middle finger and a pink coral one on the other middle finger. Her face is good looking but not very pretty. She was very quiet and very much more ladylike than her sister, a coarse rough girl with a dirty snuff-coloured handkerchief on her head, a loose black jacket and a green skirt, much too long in the front. She brought us coffee and jam and seemed very respectful to Mrs. Paton. We could see some dirty little brethren in the general living room. It is very sad to see such relations for an English gentleman.”

Mabel’s comment that Irini was ‘a fine big girl’ was made without her being aware that, at the time, Irini was 15-16 weeks pregnant. How Mabel would have relished writing about that, had she known! This fact might partly explain why Irini was reluctant to travel back to Scotland with Paton in March 1886.

With Mabel’s inquisitiveness about Irini Paton sated, she and Theodore left Kalymnos for Astypalea on Saturday March 20th, 1886.

The Olympitis’ ‘beautiful’ house on the quayside at Pothia where the family stayed while in Kalymnos and where Theodore and Mabel Bent would have met Irini. Augusta wrote : ‘It was the biggest house with the best accommodation on the island and was situated on the quayside with only a large pavement between it and the sea, which, with its anchored coloured boats, full of sponges and brilliantly coloured fishing equipment, was a sight to gladden my heart.’

The house was demolished in the 1970s and the current Olympic Hotel was erected in its place – ‘the best accommodation on the island’. The hotel is still run by members of the Olympitis family.

Return to Scotland

We know from Theodore and Mabel Bent, and from the birthplace of Paton’s first son George, that Irini did not go back to Scotland in 1886, however, Augusta’s autobiography records them being there for much of the time during the first four years of their marriage. Their daughter, Thetis, was born in November 1887 in Aberdeen followed by a son John, in 1890, born at the family seat of Grandhome.

Irini always called Paton ‘Willie’, the name used by Augusta in her wrtings.

Irini was a devout Orthodox and was unhappy not to be able to worship in her faith, there being no Greek Orthodox church in Aberdeen. She was also uncomfortable that her children were not ‘properly’ Christened in ‘that austere Presbyterian cathedral’ which she went through the motions of attending each Sunday, listening to Willie reading the lesson in his ‘carrying sonorous voice’.

The couple were still deeply in love and there were happy times in Scotland. Paton’s family and friends had welcomed Irini as its own. However, neither of them could stand the climate and Paton was never happy running the affairs of the estate. As soon as the children were old enough, he accepted an assignment for a new excavation in Asia Minor.

The house by the Aegean sea

Irini’s mother, Palia, had a property on the Turkish coast at Gümüşlük near Bodrum, where Irini and Paton’s first son George had been born. Palia owned much of the land around and a simple house existed on the property, close to the sea. She’d built a small chapel on the hill for the few local Christians. The happiest years for all the Paton family were those spent at the house. Paton and Irini’s youngest child, Augusta, or Sevastie, was also born in the house and her first few years were spent there. For Paton it was perfect. He could take himself off, sometimes for many months, and immerse himself in his work while still being able to return home, at times, for Irini and the children. For the children, it was an idyllic adventure playground and Augusta writes evocatively of those ecstatic days.

But Irini was doing other things while in Gümüşlük as well. Paton’s great-grandson, also William Paton, provides us with an insight from a publication by Paton, originally in French – “Myndos is a town which knows well how to hide its inscriptions. The inscriptions that I published in the ‘Bull. de corr. hell. (volume XIV)’ do not come from the town itself but from the surrounding area. The town and its cemeteries only provided two inscribed stones. The two that I added were found, in the final days, in the rubble of a church near the Halicarnassus Gate. We owe them to excavations carried out without my knowledge by Mrs. Paton.”

As Paton’s work in Asia Minor came to an end, the spectre of leaving Gümüşlük weighed heavily on Irini. The boys were approaching the age when boarding school in England beckoned – John had already spent time there. During the period the family were in Gümüşlük, George and John had attended a school in Kos while Thetis was schooled in Smyrna (present-day Izmir).

Irini and Augusta left Gümüşlük to meet Paton and the boys in Kalymnos. Irini was heartbroken to leave the home where she’d been so happy. She was never to see the house again.

The family came together again in the Olympitis house on the quayside of Pothia in Kalymnos, where they celebrated Christmas 1905.

Paris

But, for the ever-driven Paton, time was dragging in Kalymnos and, early in 1906, he uprooted the family in favour of the Parisian suburb of Viroflay, near Versailles. There, Irini and Augusta learned French and made friends. Irini was happy that she could go to the church of St. Julien le Pauvre note 3 . They were content with life in Viroflay.

Brittany

But, once again, Paton moved them on, this time to a villa by the sea on the coast of Brittany at Peros Guirec. Irini was never happy in the period she spent in Brittany.

A sad, sad ending

It was in Brittany that the first signs of Irini’s illness appeared; she was often in great pain. One of her kidneys was damaged and had to be removed. In October 1908, she was admitted to a hospital in Paris where the successful operation was carried out. Irini was free from the pain she’d suffered.

The day came to leave the hospital and Irini’s best friend, Delphine, was helping her to dress amid happy laughter while Paton was pacing around outside in the corridor. Suddenly Irini clutched at her chest and said in Greek ‘Pono’ note 4 . She collapsed into Delphine’s arms and died. She was 38 years old. Paton ‘went quite beserk’ and ripped his shirt to shreds in his uncontrollable grief.

The fairy-tale romance had ended. Paton was 51, George 22, Thetis 21, John 18, and Augusta just 8. Irini had been the source of all the love that had brought happiness to Paton and the family since that first vision of her, all those years ago, in a tiny boat bobbing on the waters of Pothia Bay. William Paton was a broken man.

Leave a comment about this comment

Leave a comment about this commentAccreditations

● This article was researched and compiled by Alan King.

● Mabel Bent’s diary entries are taken from the book The Travel Chronicles of Mrs J Theodore Bent Volume I. ©2015 Gerald Brisch and Archaeopress. Reproduced by kind permission. Get the book or download the e-book.

● The author wishes to thank Emmanuel N. Olympitis for his enthusiastic assistance in providing material and invaluable information for this article.

● The author wishes to thank William Paton, Paton’s great-grandson, for his suggestions and contributions from the family archives.

● Some of the material for this article was derived from the autobiography of Augusta Paton (Kemény), William and Irini Paton’s daughter. The autobiography is currently available only in Hungarian. Read a short biography of Augusta Paton.

● The images used in this article may be subject to various copyright restrictions.

Notes

Return from Note 1

Return from Note 2

Return from Note 3

Return from Note 4